I have included sex as a driving force in human life among my “demon drivers.” This is about ‘sex’ (and therefore ‘gender’) as a classification.

President Trump recently declared, “there are only two genders—male and female.” Of course, Americans rarely study any foreign languages, let alone the classical languages, so they have no idea what ‘gender’ means. Asked how many genders there are, any school child of my generation would have answered, “three—masculine, feminine and neuter.”

For thousands of years, ‘male’ and ‘female’ have been used to identify physical differences. And not just between people. Ask anyone in a DIY shop who knows about connecting pairs, how many types of coupling there are, and you should get the answer, “two—male and female.” Male couplings have external threads, while female couplings have internal threads. Or, more simply, males have bits sticking out, females have holes.

The crude sexuality of this may have predisposed some Americans to dislike the very word “sex.” (In the late nineteenth century, there were American women who hid the legs of furniture, since the sight of any leg was shocking.) So when “gender” began to be proposed as an alternative, and the real meaning of “gender” was so little known, it’s hardly surprising it caught on.

It began differently. When my wife and I visited the USA in the early 1970s, European feminism was still influential. Women whose languages actually had genders (which English doesn’t) pointed out that the terms “masculine” and “feminine” were completely arbitrary in their application. The Spanish for “a dress”, for example, is “un vestido” (because “dress” is a masculine noun). “People” are “la gente” (feminine)—even when the the people being referred to happen to be men.

This meant that the terms “masculine” and “feminine”, when applied to human qualities and behaviour, could be treated as equally arbitrary. A period of ‘gender-bending’ ensued, in the USA as well as in Europe. In 1972, my wife and I went to a play in Greenwich Village which explored the obsolescent ideas of ‘masculinity’ and ‘femininity’, and in which the central character (a woman, like all the cast) wore dungarees, cut her hair short, and expressed her views in a traditionally ‘masculine’ manner.

Some time in the late 1980s (in England, maybe earlier in the USA) the new wave of feminists started using ‘gender’ instead of ‘sex’, when referring to men and women—thinking that this was a way of emphasising that many differences between men and women were socially constructed, rather than biological.

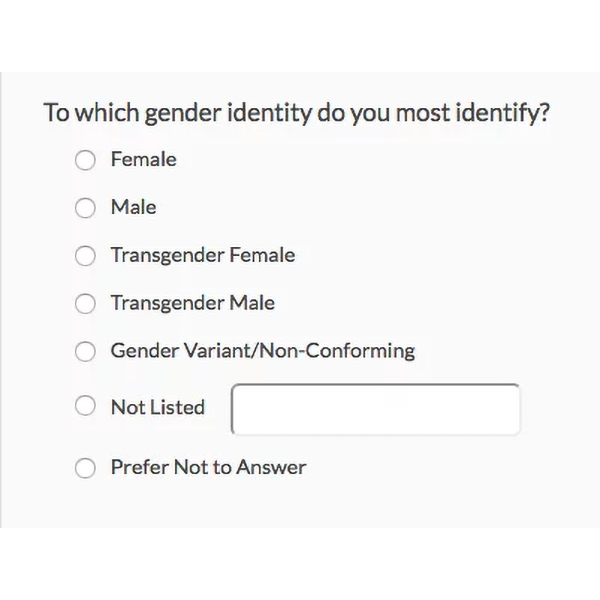

Its actual effect has been the opposite. People who would previously have been called “transsexual men” are now called “transgender women”, and their notion of womanhood is socially constructed with a vengeance. “Transgender women” tend to wear dresses and high-heel shoes, and grow their hair long. Many could be 1950s-style “feminine” women.

In other words, because of the way they are named, they help to perpetuate, for all women, an obsolete ideal. What is more, whatever they wear, transgender women perpetuate the idea that there are important differences between men and women, as such—when the whole effort of the various women’s movements of the last century or more has been to insist that, while biological differences may enforce certain constraints, and while individual men and women may differ in their nature and their abilities, there are no differences between the nature and abilities of men and women as such.

A century-old wave of progress has petered out. Willing or not, we have all signed up again to ‘Vive la difference!’